Children bear brunt of South Africa’s tuberculosis epidemic

Amid the noise of crying and moaning children, a little boy lies in a cot, curled up and silent, his eyes staring blankly at the ceiling.

His doctor, Mariaan Willemse, said he’s got a very severe form of tuberculosis meningitis – an extremely dangerous strain of brain TB that’s killing many youngsters in South Africa.

Willemse heads the children’s section of Cape Town’s

Brooklyn Chest Hospital. International health experts regard it

as one of the world’s leading TB treatment centers.

The hospital is in the epicenter of South Africa’s TB

epidemic.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), the country

has the highest rate of new TB cases annually. Thousands of

people in South Africa continue to be infected by a disease

that’s been virtually eradicated in the developed world.

TB is primarily an illness of poverty. It thrives when people

live together in large numbers in close proximity, often

surrounded by smoke in small spaces with poor

ventilation.

The WHO says every year at least 500,000 babies and children

become infected with TB worldwide and an estimated 70,000 die of

it – many in South Africa, India and China.

In a recent statement, Dr. Maria Raviglione, director of the

WHO’s Stop TB Department, said, “We have made

progress on TB: death rates are down 40 percent overall compared

to 1990 and millions of lives have been saved.

But unfortunately, to a large extent, children have been left

behind, and childhood TB remains a hidden epidemic in most

countries.”

Willemse’s hospital is so overburdened with young patients

that it cannot help all the children who are contracting TB.

“We always have a waiting list. So as the one goes out

there’s already somebody (else) waiting to come in,”

she told VOA, and added that Brooklyn Chest is thus forced to

admit only the sickest children.

Half will die

In adults, TB mostly attacks the lungs. But Willemse explained

that in small children, with their undeveloped bodies, it

concentrates in the lymph nodes. “This allows the TB to

pass more easily into the brain,” she said.

Looking down at another of her tiny patients, Willemse

commented, “He was basically in a coma when he arrived

here five months ago. Before he got sick, he was a normal

four-year-old boy running around. Now he’s cortically

blind…His eyes are working but his brain cannot interpret

the images…. He’s (deaf) and he’s also a

quadriplegic. And at this stage also he’s unable to

swallow so he’s being fed with a tube.”

Like many of her young patients, when the boy arrived at her

surgery he was unconscious. The prognosis for children with TB

meningitis at such an advanced stage is not good, said the

doctor.

“Fifty percent of them will die of the disease and the

other 50 percent will have severe (brain) damage. They become

spastic quadriplegic, meaning that their arms and legs

don’t work and are very stiff. They’ll probably have

to be looked after at home for the rest of their lives,”

said Willemse.

Misdiagnoses

Doctors often misdiagnose TB meningitis, which adds to the

pressure the disease is putting on South Africa’s public

health system. “It’s easy to mistake it for other

common childhood illnesses. It usually starts with just a bit of

a headache; the smaller child may be vomiting, having a

fever,” said Willemse.

She added that doctors often mistakenly diagnose children who

have TB, thinking they have conditions like middle ear

infection. They then prescribe antibiotics that obviously

don’t heal the youngsters.

“In two days the child is still not eating, is still

vomiting, is now starting to become very sleepy, lethargic, and

doesn’t want to play anymore. But the mom often

(doesn’t) go back to the same (doctor) because it

didn’t work (the first time) so she goes somewhere else

– up until the child has convulsions. And then they know

that this is something serious….”

But by this stage, said Willemse, it’s often too late to

save the child from permanent disability, or even death.

She said that perhaps the most difficult part of her job is to

tell parents that their previously healthy child will never be

the same again, because of TB meningitis.

“I can’t tell them upfront, ‘Your child

won’t be able to walk or won’t be able to

sit.’ I can’t say that, but I can tell them that

‘I already see there is a lot of brain damage. And I

already know that your child is not going to be normal; your

child did have severe damage.’ And that’s not nice

at all. It’s a heavy burden sometimes. One sometimes lies

awake at night, and you pray for them.”

‘A manmade disease’

In another corner of the hospital’s children’s ward,

Willemse gestured towards an infant in a cot and explained,

“She’s six months old. She’s been here for a

month. The mommy died two days after the baby was born. She was

born very prematurely. This child’s mother had TB while

she was pregnant.”

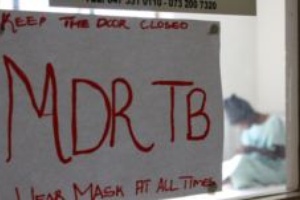

The mother infected her child with another potentially fatal

kind of TB, namely multidrug resistant, or MDR, TB.

“It’s a manmade disease,” said Willemse. It

has developed as a result of people with normal TB not

completing their treatment.

“The drugs have side effects, such as nausea, and so many

people stop taking them. Many adults default with their

treatment, after which the TB germ develops resistance to the

routine antibiotics with which we treat the condition,”

the doctor explained. “They then infect their children

with MDR (TB).”

Six months of treatment usually wipes out normal TB. But MDR TB

patients need 18 months of medication to heal. They’re

hospitalized and injected with drugs for six months, followed by

12 months of treatment at a local clinic.

The injected medicines have dangerous side effects, especially

for very young patients. They can make the children go deaf.

They can damage their kidneys and their thyroid glands.

But Willemse emphasized that the drugs still offer MDR TB

sufferers’ the best chance of survival.

Losing the battle

After decades of government programs, as well as local and

international interventions aimed at ending South Africa’s

TB scourge, Willemse sees no sign of it abating soon. In fact,

based on her experience, she said it’s getting worse.

“More than half of the children admitted to Brooklyn Chest

have MDR TB, and that’s just the tip of the iceberg. We

are losing the MDR battle,” she said.

Giving reasons for this, Willemse said cases of MDR TB

aren’t picked up in time at South African clinics. In

addition, TB patients aren’t being counseled properly at

many public health facilities. As a result, she said, they

don’t realize how infectious the disease is and how

important it is for them to complete their treatment - and how

easily they can pass TB on to their children.

Willemse said TB patients themselves are also responsible for

spreading the disease. “I think the crux is that the adult

who is coughing and losing weight must go to the clinic and must

be tested for TB. But it’s a major problem that there are

people who are still unwilling to be tested.”

Willemse said TB infection rates in South Africa will drop in

the future if health services improve but predicted that the

country will never be a TB-free society.

There’s too much poverty, she said, and this means the

conditions that allow TB to thrive will endure well into the

future.

More than 1,000 miles away from Brooklyn Chest Hospital, another

doctor, Taryn Gaunt, is also dealing with a flood of TB cases in

Oliver Tambo District.

She said, “South Africa can implement all the

interventions it wants to fight TB. But at the end of the day,

only when the standard of living radically improves in the

country will we be able to talk about the possible eradication

of TB. Until them, we’re locked into this terrible cycle

where we invest so much money in trying to fight a disease that

just seems to have no end.”

VOA

http://www.voanews.com/content/children-bear-brunt-of-tuberculosis-epidemic/1213097.html