The use of bedaquiline in regimens to treat drug-resistant and drug-susceptible tuberculosis: a perspective from tuberculosis-affected communities

Community voices on bedaquiline's use to treat drug-resistant tuberculosis and future development as a potential treatment for drug-susceptible disease have been largely unheard.

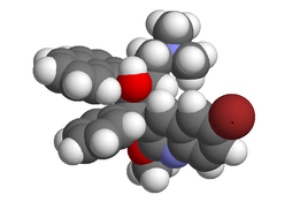

In December, 2012, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved bedaquiline for the treatment of pulmonary drug-resistant tuberculosis (1). WHO has issued normative guidance on bedaquiline (2), which is available on the market in the USA and through compassionate use in other countries. As the first new drug from a novel class approved to treat tuberculosis in more than 40 years, bedaquiline's implications for improving treatment of drug-resistant tuberculosis and possible application to create shorter first-line regimens for treatment of drug-susceptible tuberculosis is still unclear. Existing drugs must be taken for months (drug-susceptible tuberculosis) or years (drug-resistant tuberculosis), burdening patients and health systems; even then, cure rates for drug-resistant disease range from 11% to 79% dependent on the extent of resistance (3, 4). However, community voices on bedaquiline's use to treat drug-resistant tuberculosis and future development as a potential treatment for drug-susceptible disease have been largely unheard. We provide a community perspective on this issue and list seven questions concerning bedaquiline's safety that researchers should answer before the launch of clinical trials of bedaquiline for drug-susceptible tuberculosis.

Developed by Janssen, bedaquiline (Sirturo) received accelerated approval from the FDA based on two phase 2b studies of 440 people with multidrug-resistant tuberculosis (5, 6). More patients who received bedaquiline, rather than placebo, in combination with other drugs for drug-resistant tuberculosis converted their sputum cultures from positive to negative after 8 and 24 weeks of treatment. The proportion of culture conversion at week 8 was 47·6% in the bedaquiline group and 8·7% in the placebo group, whereas the proportion at week 24 was 81% for the bedaquiline group versus 65·2% for the placebo group (5, 6). Culture conversion at 2 months is a common surrogate measure of treatment success.

The approval of bedaquiline came with several caveats. Drug side-effects linked to bedaquiline include an increased number of adverse events tied to liver toxicity; QT prolongation, a potentially serious disturbance in the heart's electrical rhythm; and an accumulation of phospholipids in cells (7). Bedaquiline's long half-life means that these and other side-effects could pose risk to patients even after discontinuation of therapy. Most concerning, patients taking bedaquiline with a background regimen of other second-line drugs had a higher risk of mortality than did those taking placebo with background regimen. In a randomised, placebo-controlled trial (5, 6), ten of 79 patients in the bedaquiline-containing group died (13%) versus two of 81 patients in the placebo group (2%). In a separate, single-group, open-label trial (5), 16 of 233 patients (7%) receiving bedaquiline died. Most of these deaths occurred months after patients received their last bedaquiline dose, but bedaquiline's long half-life means that the drug's possible contribution to the patient deaths cannot be excluded (6).

Safety when using bedaquiline to treat drug-resistant tuberculosis remains an important concern; however, we believe that this consideration needs to be placed in the context of the shortcomings and toxic effects of present regimens for drug-resistant tuberculosis. Even in the absence of data from phase 3 trials, the existing safety and efficacy data for bedaquiline are supported by more high-quality clinical investigations (11 phase 1 trials and three phase 2 trials) than exist for any other drug used to treat drug-resistant disease. Most of the existing second-line drugs were developed decades ago and have insufficient robust efficacy and safety data from randomised clinical trials. Bedaquiline is entering a suite of second-line drugs that carry severe toxic effects requiring careful monitoring. If submitted to stringent regulatory authorities today, many of the second-line drugs used to treat drug-resistant tuberculosis might not receive approval. Bedaquiline offers an important addition to existing second-line regimens and, in our view, merited accelerated approval by the US FDA. Yet countries have been slow to approve bedaquiline, leaving many patients with drug-resistant tuberculosis either without access to this potentially life-saving treatment, or reliant on unsustainable compassionate use mechanisms. We urge countries to expedite the review and approval of bedaquiline for the treatment of drug-resistant tuberculosis, as indicated by the US FDA, and to work with WHO and national tuberculosis programmes to prepare for the rollout of this new drug.

Although bedaquiline offers an important new treatment for patients with multidrug-resistant tuberculosis with extensive resistance or toxicities to other second-line drugs, the increased risk of mortality raises a serious question about the ethics of studying bedaquiline as a component of experimental therapies for drug-susceptible tuberculosis, an idea being considered by several tuberculosis research consortia. Answering this question requires weighing the potential benefits of incorporating bedaquiline into first-line treatment—namely, the opportunity to shorten treatment timelines—against the risks to patients suggested by the available mortality and toxicity data. As elected members of the Community Research Advisors Group (CRAG), an international, community-based advisory body to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's Tuberculosis Trials Consortium (TBTC), the decision about whether to study bedaquiline as a component of first-line therapy stands to directly affect the communities with which we work.

Tuberculosis drug developers and research consortia such as the TB Alliance, the TBTC, the AIDS Clinical Trials Group, and the European and Developing Countries Clinical Trials Partnership are seeking ways to shorten treatment for drug-susceptible tuberculosis from 6 months to 4 or fewer months with use of new drug combinations. Data from Janssen's phase 2b trial indicated that regimens containing five drug-resistant tuberculosis drugs plus bedaquiline resulted in faster sputum conversion than did regimens without bedaquiline, which suggests that bedaquiline could enable shorter first-line therapies. The TB Alliance has completed a phase 2a study assessing bedaquiline's early bactericidal activity in several drug combinations (8).

CRAG members discussed whether bedaquiline should be given to a broader patient population under first-line therapy after a review of the briefing document that Janssen submitted to the FDA (2) and completing a thought exercise in which members wrote informed consent forms as if enrolling patients with drug-susceptible tuberculosis into a hypothetical bedaquiline-containing first-line regimen. In reviewing the briefing document, CRAG members took special note of the two patient deaths in Janssen's phase 2b trial related to liver toxicities. WHO guidance indicates that bedaquiline can be given to patients with mild to moderate hepatic impairment together with appropriate monitoring (2). Hepatitis B and C and heavy alcohol use are common in many of the regions most heavily affected by tuberculosis, including eastern Europe and southern Africa. Standard of care and the capacity to monitor toxicities differ widely worldwide, which means that drugs with poorly defined risks of liver toxicity might not be appropriate for first-line treatment for tuberculosis in all communities. Bedaquiline's long half-life might require extending toxicity monitoring beyond duration of treatment, which could prove untenable in resource-limited environments.

Clinical research ethics require that investigators begin their studies in a state of equipoise, or hold genuine uncertainty about the relative therapeutic merits of each study group (9). After completion of the informed consent exercise, the CRAG questions whether investigators would truly be in equipoise when giving bedaquiline to patients with drug-susceptible tuberculosis in view of the higher potential risk of mortality and the wealth of safety data and experience with existing first-line drugs. Patients with tuberculosis already have access to first-line drugs that are safe, effective (capable of cure when taken faithfully), affordable, and well integrated into the WHO Essential Medicines List and country-specific lists of essential medicines. Although the long duration of first-line therapy complicates adherence, safety and affordability should not be sacrificed for speed when new drugs under question might carry risks to patient survival.

At the same time, we acknowledge that clinicians treating patients with tuberculosis have few drugs with which to work, and that use of bedaquiline as part of first-line therapy might produce a unified treatment pathway for drug-susceptible and drug-resistant tuberculosis, simplifying treatment for millions of patients.

In view of these concerns, the CRAG believes that the following questions should be answered before the inclusion of bedaquiline in trials to shorten treatment for drug-susceptible tuberculosis. Do the occurrences and causes of deaths captured by the registries of patients receiving bedaquiline or by future clinical trials differ from those observed in the phase 2 studies or in patients in the same setting not taking bedaquiline? Do the occurrences and nature of adverse events captured by the patient registries or by future clinical trials differ from those observed in the phase 2 studies or in patients in the same setting not taking bedaquiline? What is the ideal dose and dosing schedule to achieve minimal risk to the patient while still offering the potential to shorten treatment? How much of the risk associated with bedaquiline is related to its long half-life? In view of bedaquiline's long half-life, how long should patients be monitored after completion of treatment? Can we establish a specific threshold for liver function that constitutes an exclusion criterion for patients with liver toxicity concerns? In view of bedaquiline's effect on the QT interval, should some patient populations be excluded from initial studies?

In enumerating these questions, we do not intend to hamper research, but instead to protect the interests of patients with drug-susceptible tuberculosis in the face of incomplete safety information. Research consortia wishing to assess bedaquiline in experimental regimens for drug-susceptible tuberculosis need to carefully monitor patient safety data as they become available through patient registries, the drug's wider use outside the USA, and future clinical trials. This monitoring should occur in close collaboration with tuberculosis-affected communities and civil society to ensure that the communities asked to participate in drug trials are well informed of the potential risks and benefits. The carefulness of this monitoring should be reflected in the inclusion and exclusion criteria for future trials, all of which must develop robust systems for collection of patient information before, during, and after bedaquiline administration.

As the beneficiary of FDA-accelerated approval, Janssen has an obligation to inform the ongoing debate. Many civil society organisations representing tuberculosis-affected communities supported Janssen's application to the FDA on the basis of data from the phase 2b trials. We now call on Janssen to make safety information from the patient registries immediately available to public research consortia and to expeditiously begin studies informing bedaquiline's use in people with hepatitis B and C, and in people who misuse drugs and alcohol. Janssen should also present mortality and toxicity data from the cohort of patients who have received bedaquiline under compassionate use and commit to finishing the phase 3 study of bedaquiline for treatment of drug-resistant tuberculosis before the 2022 deadline set by the FDA.

The CRAG urges researchers to answer the above questions about bedaquiline's safety before beginning trials of bedaquiline as a component of first-line therapy. Without answering these questions, we do not believe that researchers can approach the study of bedaquiline as a potential treatment for drug-susceptible tuberculosis from a position of true equipoise.

Contributors

All authors contributed to the conceptualisation of this Viewpoint. MWF wrote the first draft and incorporated comments from other authors. All authors revised the paper for important intellectual content, reviewed the final draft, and agreed on the decision to publish. The decision to submit the Viewpoint for publication was reached unanimously by members of the TBTC Community Research Advisors Group. LRM and DN serve as cochairs of this advisory body, which includes nine elected members from communities with TBTC trial sites (FA, CC, CL, LRM, DN, BS, DS, NS, and ETdSFF) and two unelected representatives from tuberculosis drug trial sites outside the TBTC network (NB and TE). MWF is employed by Treatment Action Group, and provides technical and administrative support to the CRAG, but does not serve as an elected, voting member.

Declaration of interests

MWF has received grants from the Global Alliance for TB Drug Development and the Stop TB Partnership for projects outside the submitted work. All other authors declare no competing interests. The CRAG receives limited funds from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to support its work with the TBTC. CRAG members receive no compensation for their involvement with CRAG, and all CRAG activities are undertaken on a volunteer basis. MWF is employed by Treatment Action Group and provides technical and administrative support to the CRAG; Treatment Action Group has multiple funding sources. No CDC or other public funding was used for the creation of this Viewpoint.

Acknowledgments

We thank Reuben Granich for a helpful review of an early draft, and Lindsay McKenna for her support preparing this document. The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors.

References

1 . J&J Sirturo wins FDA approval to treat drug-resistant TB. Bloomberg News. Dec 31, 2012. http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2012-12-31/j-j-sirturo-wins-fda-approval-to-treat-drug-resistant-tb.html. (accessed March 24, 2014).

2 . In: The use of bedaquiline in the treatment of multidrug resistant tuberculosis expert group meeting report. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2013: 1-31. http://www.who.int/tb/challenges/mdr/bedaquiline/en/index.html. (accessed March 24, 2014).

3 . Treatment outcomes among patients with multidrug-resistant tuberculosis: systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis 2009; 9: 153-161. Summary | Full Text | PDF(201KB) | PubMed

4 . Long-term outcomes of patients with extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis in South Africa: a cohort study. Lancet 2014; 383: 1230-1239. Summary | Full Text | PDF(486KB) | PubMed

5 FDA. Division of Anti-Infective Products. Office of Antimicrobial Products. Briefing package. Sirturo (bedaquiline 100 mg tablets) for the treatment of adults (≥18 years) as part of combination therapy of pulmonary multi-drug resistant tuberculosis (MDRTB). NDA 204-384. Silver Spring: FDA Anti-Infective Drugs Advisory Committee Meeting, 2012. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/AdvisoryCommittees/CommitteesMeetingMaterials/Drugs/Anti-InfectiveDrugsAdvisoryCommittee/UCM329258.pdf (accessed March 24, 2014).

6 . The diarylquinoline TMC207 for multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. N Engl J Med 2009; 360: 2397-2405. PubMed

7 . An activist's guide to bedaquiline. New York: Treatment Action Group, 2013. http://www.treatmentactiongroup.org/tb/publications/2013/activist-guide-bedaquiline. (accessed March 24, 2014).

8 Diacon A, Dawson R, Van Niekerk C, et al. 14 day EBA study of PA-824, bedaquiline, pyrazinamide and clofazimine in smear-positive TB patients. 2014 Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections; March 5, 2014; Boston, MA, USA. Abstract 97LB.

9 . Equipoise and the ethics of clinical research. N Engl J Med 1987; 317: 141-145. PubMed

By Laia Ruiz Mingote BA a, Dorothy Namutamba BS a, Francis

Apina MBA a, Nomampondo Barnabas a, Carmen Contreras BS a,

Taharqa Elnour BS a, Mike Watson Frick MSc b, Cynthia Lee MS a,

Barbara Seaworth MD a, Debra Shelly a, Natalie Skipper BA a,

Ezio Tavora dos Santos Filho MSc a

a Community Research Advisors Group, New York, NY, USA

b Treatment Action Group, New York, NY, USA

Source:

The Lancet